Indigenous and farming communities say Vancouver-based Fortuna Silver Mines is responsible for environmental contamination and increased violence in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Heavy rains caused the overflow of a tailings dam operated by Canadian company Fortuna Silver Mines in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca on Sunday, October 7, contaminating the Coyote Creek and threatening the primary source of water for farming communities in the Central Valleys region.

Residents of Magdalena Ocotlán take water samples. Photo: Community of Magdalena Ocotlán.

Authorities of the Indigenous Zapotec town of Magdalena Ocotlán informed that on the morning of October 8, residents observed a stream of white water in the tributary of the Coyote Creek that passes through their community, located 5 kilometers downriver from the “San José” gold and silver mine in the neighboring community of San José del Progreso. Local officials insist that the source of contamination is a tailings dam where the Vancouver-based precious metals producer stores waste from its underground mine, in commercial production since 2011.

The affected creek passes no more than ten meters from the primary drinking water well in Magdalena Ocotlán, and ultimately flows into the Atoyac River, the most significant tributary in Oaxaca City. Agrarian and municipal authorities of Magdalena Ocotlán, where the majority of residents earn a living through agriculture and cattle-raising, expressed alarm at the possible environmental and health impacts of the spill.

On Monday they presented water samples and photographs to Mexico’s Federal Bureau of Environmental Protection (PROFEPA) in the hopes of initiating an investigation, and on Tuesday the Bureau sent a “verification brigade” to assess possible contamination. Local officials say the brigade met with management of the Cuzcatlán mining company, Fortuna Silver’s 100%-owned Mexican subsidiary, but did not seek out a meeting with representatives of the community. On Friday, PROFEPA confirmed that mud and fine mining waste from the San José tailings dam had overflowed directly into the Coyote Creek.

Residents’ demands went beyond the assessment of damages and the adoption of mitigating measures, calling for the closure of the Sn José mine and a moratorium on the exploitation of mineral resources in Oaxaca:“We demand that the Federal Government not issue any more mining concessions, because these imply environmental impacts and irreparable risks for the population,” residents declared in an statement.

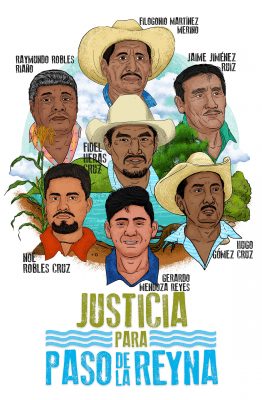

Fortuna Silver Mines, listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the symbol FVI, began exploratory activities at the “San José” mine in 2006, after signing usufruct agreements with individual landowners. Tension over the San José mine came to a head in 2012 with the assassination of two anti-mining activists from the community of San José de Progreso. In January, as opponents of the mine gathered for a protest in defense of their water resources, a municipal police officer fired into the crowd, killing local resident Bernardo Méndez Vásquez. In March, gunmen opened fire on members of the environmental and human rights group the Coalition of United Peoples of the Ocotlán Valley (CPUVO) as they traveled home from the Oaxaca airport, killing Indigenous Zapotec land defender Bernardo Vasquez Sánchez.

To date, no one has been charged for these murders, and a Civilian Observation Mission conducted by national and international organizations in November 2012 concluded that “municipal and state authorities and Fortuna Silver Mines share a high level of responsibility for the attacks against inhabitants of the community.” The mission’s final report also denounced the control of the community by armed groups that are connected to municipal authorities and defend the interests of the mining company.

Soil and vegetation are covered by white residue following the overflow of the tailings facility at the “San José” mine. Photo: Emilio Morales Pacheco, NVI Noticias.

Soil and vegetation are covered by white residue following the overflow of the tailings facility at the “San José” mine. Photo: Emilio Morales Pacheco, NVI Noticias.

Last week, residents of Magdalena Ocotlán, San José del Progreso, and neighboring communities denounced the contamination of their water and other violations committed by Fortuna Silver Mines at the first “People’s Trial against the State and Mining Companies in Oaxaca.” Organizers said the symbolic tribunal, promoted by affected communities in collaboration with national and international human rights organizations, aims to raise awareness around the violation of rights caused by the imposition of mining projects, as well as to articulate movements against extractive activity in Oaxaca, Mexico’s most biodiverse and most Indigenous state.

“People are worried; they are no longer drinking our water,” declared an agrarian authority of Magdalena Ocotlán before a crowd of several hundred people, as he held up a plastic bottle filled with thick, beige liquid collected from the Coyote Creek. “Just 10 meters from the river is the well that supplies water to my town, my people; and the municipal authority has already warned residents not to consume water from the well; but the miners say they don’t pollute.”

Villagers said that while the overflowing water has receded, a strong sulfuric odor lingers, and a thin, white layer of residue has stained soil and vegetation in the affected area, which includes farmland, a watering hole for animals, and an aquifer recharge zone.

Representatives of the local water commission have temporarily suspended the distribution of water to the population pending water quality tests. At the people’s trial on Thursday, authorities of Magdalena Ocotlán and representatives of Oxfam Mexico, the international non-governmental organization and a co-organizer of the event, were seeking a laboratory to test water samples collected by community members, as there is no facility certified to carry out such analyses in Oaxaca.

Soil and vegetation are covered by white residue following the overflow of the dry stack tailings facility at the “San José” mine in Oaxaca, Mexico. Photo: Emilio Morales Pacheco, NVI Noticias.

It was not until Thursday that Fortuna Silver Mines issued a statement informing that high rainfall had caused a contingency pond to overflow at the dry stack tailings facility at the San José mine. Yet the company emphasized that this is a cyanide-free operation and that “no industrial process water was discharged in this incident.”

The spill did not appear to impact production levels for Fortuna, which issued a simultaneous press release advertising a nearly 15% increase in gold and silver tonnage for the third quarter of 2018. The company operates in the state of Oaxaca with four subsidiaries and approximately 26 concessions totaling over 800 square kilometers—an area more than 10 times the size of Oaxaca’s capital city.

Speakers at the tribunal event said that while Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization requires the consent of Indigenous peoples regarding projects that may affect their communities, in Oaxaca Indigenous towns like Magdalena Ocotlán and San José del Progreso were never consulted regarding the Mexican government’s concession of their land to Fortuna Silver Mines. Mexico and Canada are both signatories of the binding international convention.

Moreover, participants noted that nearly 73% of mining companies operating in Mexico are based in Canada, and highlighted the responsibility of foreign governments in preventing the violation of Indigenous and human rights. “The government of Canada gives subsidized loans to its companies,” said Daniel Cerqueira, a Brazilian lawyer and expert on Indigenous rights at the Due Process Law Foundation (DPLF) in Washington, D.C., who formed part of the “jury” at the People’s Trial. “When a State allows companies to be incorporated into its legal system but does not provide guarantees against their activities abroad, it could benefit from outsourcing human rights violations to other territories.”

At the tribunal event, communities and organizations vowed to hold Fortuna Silver Mines accountable for the spill and to continue organizing against the violation of their rights by mining companies in Oaxaca.

![]()