On June 19th, 2016, prolonged tensions due to the Mexican government’s educational reform came to a head in Asunción Nochixtlán, a Mixtec municipality an hour’s drive from Oaxaca City, where at least 8 people were killed and 226 civilian injured during protests. During this incident, the government of Oaxaca—a southern territory known for Indigenous and popular resistance—once again proved that it does not hesitate to use excessive force to impose its will.

30 months after the Nochixtlán massacre, justice has yet to be served. On the contrary, the state has repeatedly denied authorities’ responsibility, instead placing the blame for confrontations on local residents and demonstrators. “Neither the victims nor their families have had full access to justice or health care,” explains the local NGO Codigo DH; “no actions have been taken to comprehensively repair the damages they suffered.”

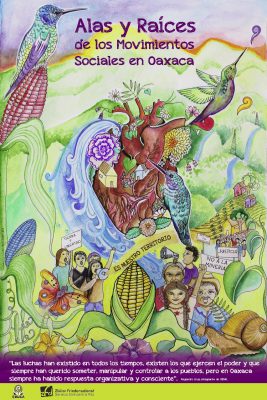

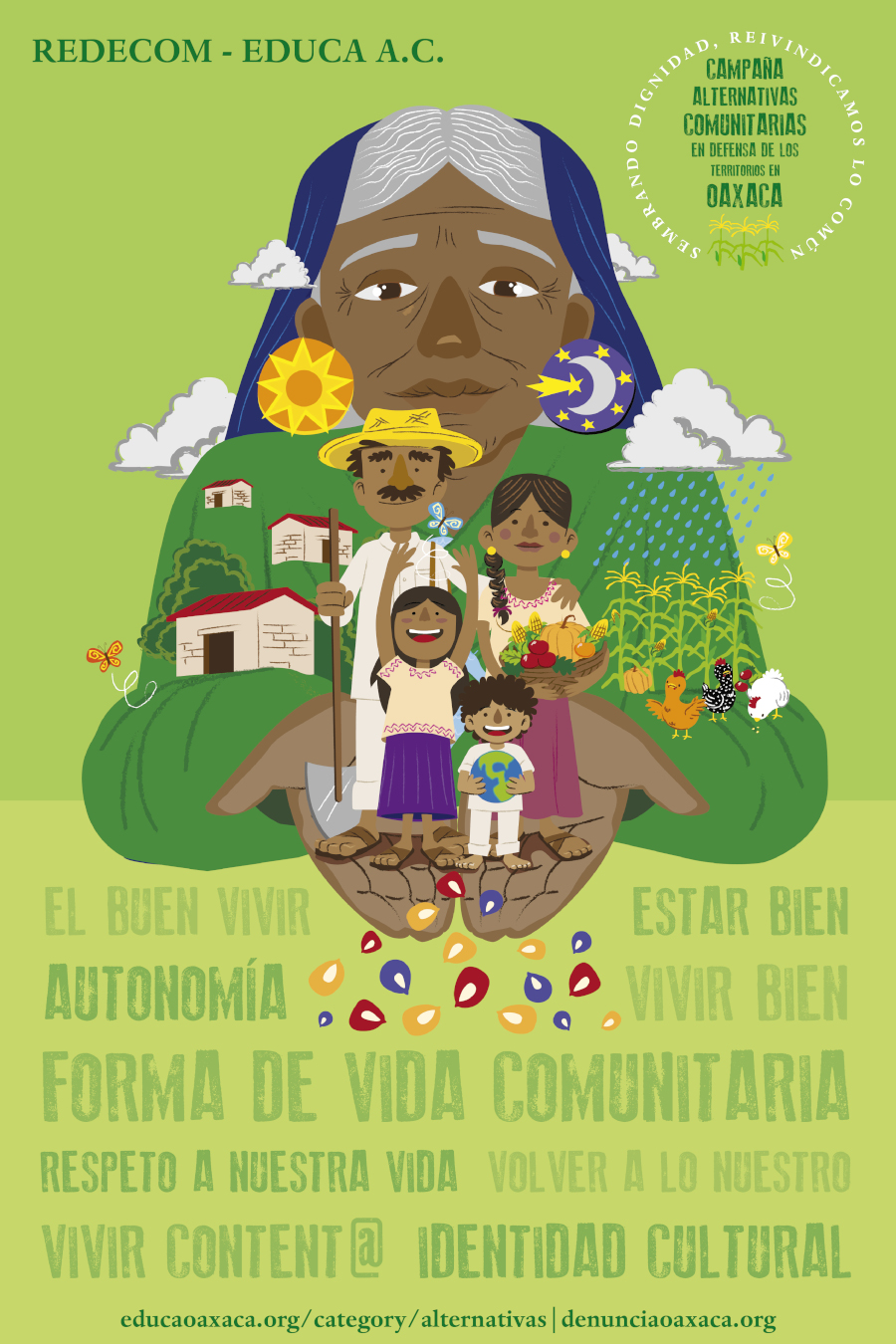

In November, as the UN conducted a comprehensive review of human rights in Mexico, Oaxacan civil society organizations again turned their gaze to Nochixtlán as an emblematic case of state violence and impunity, which they say worsened during the last presidential and gubernatorial terms. In the context of the UN Human Rights Commissions’ Universal Periodic Review (UPR), Oaxaca NGOs including EDUCA A.C. published the shadow report, “Under attack. Human Rights in Oaxaca 2013-2018”, which cites the Nochixtlán massacre in analyses of worsening attacks against human rights defenders, violence as a key strategy for the imposition of structural reforms, and the criminalization of social protest in Oaxaca.

The article that follows examines the 2016 confrontation and its aftermath, against the backdrop of the UNHCR’s current recommendation for improving human rights in Mexico. While former President Enrique Peña Nieto has been denounced for failing to heed the UN’s 2013 recommendations, this year’s proposals will land on the desk of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who will be tasked with implementing long-awaited reforms in coordination with civil society groups.

We hope the following text serves as a tool not only for evaluating the rollback of human rights in Mexico from 2013-2018, but also for analyzing the path forward at this critical juncture. Is justice still possible for the victims of Nochixtlán? How will civil society work to ensure that the UPR recommendations are heeded going forward?

Nochixtlán: an emblematic case of human rights violations in Oaxaca

The Nochixtlán protests arose in response to the Educational Reform that was passed by the Mexican Congress in 2013, as part of a broader package of structural reforms including the partial privatization of Mexico’s state-run oil company and a corporate tax reform. The constitutional reform linked teacher salary and job security to expanded professional and student testing, extended the school day with some but not proportional increased compensation for teachers, and enacted measures to increase “school autonomy”, giving principals more control over hiring and firing and opening the door to increased corporate funding.

The government claimed the reform was necessary to increase student achievement, which is poor in Mexico despite relatively high spending on education in comparison with other OECD countries. However, many civil society organizations, academics, teachers’ unions, and parent organizations claimed the educational reform was in reality a labor reform, which invoked the worthwhile goals of “accountability” and “quality” in order to justify changes in teachers’ employment conditions and reduce collective bargaining power. Efforts to pass these reforms were accompanied by an aggressive campaign that depicted teachers’ unions as corrupt and self-interested. While the sale and inheritance of teaching jobs under union control has been documented, much of the government’s discourse has been discredited as misleading and opportunistic. In short, the reform violated workers’ rights, as many teachers lost their jobs without compensation.

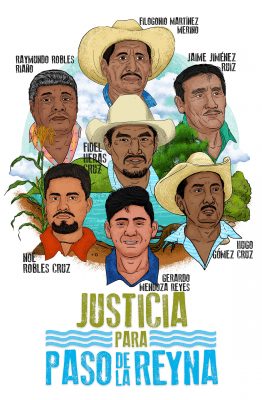

This is why in June of 2016 teachers and community members gathered in Nochixtlán to protest the reform. Previously, protests against the reform had been led by members of the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE)—a dissident wing of the National Educational Workers Sindicato (SNTE), and its regional unit, Oaxaca’s Teachers’ Union Section 22. The arrest of CNTE leaders in June 2016 kicked off a series of highway blockades throughout Oaxaca State, including a strategic roadblock in the municipality of Nochixtlán, which connects Oaxaca’s capital to Mexico City. Teachers and their allies also maintained blockades in Huitzo, Hacienda Blanca and the intersection of Viguera, strategic points for the flow of traffic in the greater metropolitan area of Oaxaca City.

This led authorities to convene a major police operation against protestors on June 19, with the stated aim of “liberating roadways”. While the operation had been announced ahead of time, the task force did not precede according to the scheduled time plan: police invaded early in the day, at a time when the majority of those present were civilians.  Police did not provide prior warning regarding the use of force, nor did they offer civilians an opportunity to evacuate. While the federal government issued a press release that same day stating that police forces have not been armed, photographs and videos proved that police was indeed armed and fired live rounds. To date authorities have denied responsibility for armed attacks on civilians, which left a total of 8 people dead and numerous injured. Moreover, approximately 21 cases of arbitrary detention have remained in impunity.

Police did not provide prior warning regarding the use of force, nor did they offer civilians an opportunity to evacuate. While the federal government issued a press release that same day stating that police forces have not been armed, photographs and videos proved that police was indeed armed and fired live rounds. To date authorities have denied responsibility for armed attacks on civilians, which left a total of 8 people dead and numerous injured. Moreover, approximately 21 cases of arbitrary detention have remained in impunity.

2016-2018: Impunity and violence reign

Since the 2016 massacre, survivors organized in the June 19 Victims’ Committee (COVIC) have repeatedly suffered attacks and assassination attempts due to their efforts to hold authorities accountable.

On March 5, 2017, an unidentified armed man shot 6 bullets at the vehicle of COVIC president Santiago Ambrosio Hernández as he drove his car from Nochixtlán to the municipality of Apoala. Hernández survived but suffered injuries to his leg. On the night of March 19, 2017, during a conference of independent and community radio stations in the municipality of Asunción Nochixtlán, armed individuals opened fire in front of the home of COVIC member Felipe Montesinos. In an interview, Montesinos said the intimidation was the result of the committee’s ongoing denunciations of the grave human rights violations committed in Nochixtlán. In July 2017, armed individuals again opened fire on a truck carrying members of COVIC and Oaxaca’s Teachers’ Union Section 22. In April 2018, COVIC president Santiago Ambrosio Hernández was found in his room with his hands and feet tied, and with signs of torture all over his body.

In October 2017, the National Human Rights Commission’s (CNDH) published a 561 page official report on the events of June 19, 2016. However, human rights organizations including Codigo DH, Fundar, and Article 19, have criticized the CNDH not only for failing to reach a decisive conclusion, but also for omitting cases of torture and sexual violence. Moreover, the report contributed to the incrimination of victims “by justifying extrajudicial execution and concluding that the use of lethal force was appropriate.” To date, COVIC, the Teachers’ Union Section 22 and human rights organizations continue to demand justice for the victims of the Nochixtlán massacre, in the face of insitional obfuscation and impunity.

2018 Citizens’ Report: Recommendations for improving human rights in Oaxaca

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR), created by the UN Human Rights Council in 2005, responds to the need for an impartial, international mechanism for the evaluation of human rights, especially in the context of episodes of unpunished state violence such as the Nochixtlán massacre. The UPR addresses all human rights via the peer evaluation of UN Member States, which is informed by the input of civil society organizations regarding the gravest human rights issues in their country. It is in this context that EDUCA A.C. collaborated with allied organizations to publish “Under attack. Human Rights in Oaxaca 2013-2018”, ahead of UN’s evaluation of human rights in Mexico on November 7, 2018. The report highlights increased institutional violence and impunity during this period and proposed recommendations for the council’s consideration. Here we highlight the key recommendations related to the Nochixtlán victims’ ongoing fight for justice:

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR), created by the UN Human Rights Council in 2005, responds to the need for an impartial, international mechanism for the evaluation of human rights, especially in the context of episodes of unpunished state violence such as the Nochixtlán massacre. The UPR addresses all human rights via the peer evaluation of UN Member States, which is informed by the input of civil society organizations regarding the gravest human rights issues in their country. It is in this context that EDUCA A.C. collaborated with allied organizations to publish “Under attack. Human Rights in Oaxaca 2013-2018”, ahead of UN’s evaluation of human rights in Mexico on November 7, 2018. The report highlights increased institutional violence and impunity during this period and proposed recommendations for the council’s consideration. Here we highlight the key recommendations related to the Nochixtlán victims’ ongoing fight for justice:

- Cancel the Education Reform

The first recommendation of the citizens’ report is to “repeal the educational reform and open a broad process of consultation with various educational actors regarding the right to education for girls, boys and young people that addresses cultural differences and social and economic inequalities in Mexico.” During his first weeks in office, President López Obrador sent Congress an initiative to cancel the Education Reform and replace it with proposals developed in collaboration with Mexico’s Teachers’ Union. Initial proposals for an alternative educational plan include eliminating teacher evaluations and offering free public education.

- Protect human rights defenders

The citizens’ report highlights increasing attacks against human rights defenders from 2013 – 2018. In particular, the criminalization of human rights defenders has worsened since the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) regained power of Oaxaca’s state government in 2017. Moreover, the Human Rights Omsbudsman of Oaxaca has repeatedly aligned itself with the government, leaving many cases like Nochixtlán in impunity.

Official data mention at least 124 grievances committed against at least 76 human rights defenders in Oaxaca from January to September of 2016. In an alarming 64.5% of these cases, the perpetrators of aggression were public servants employed by the government. Though official data exclude all attacks related to the Nochixtlán case, it is worth noting that the increase in attacks on human rights defenders is directly related to the federal government’s implementation of structural reforms. “The attacks are part of a systematic policy”, explain the authors of the report.

An investigation by the Mexican human rights consortium Red TDT found that many attacks against human rights defenders are correlated with opposition to structural reforms, including energy, mining, telecommunications and educational reforms. In 2016, according to information from the Ombudsman’s Office, the majority of aggrieved persons in Oaxaca (29 out of 76) were union members who opposed the educational reform. In 2017, land defenders accounted for the greatest number of attacks (39% of the cases); the second most affected sector (33% of the cases) was comprised of citizens who suffered repression due to their efforts to access justice—an increase explained by the attacks on those seeking justice for the Nochixtlán massacre, including members of COVIC.

The Oaxaca citizens’ report recommends that the perpetrators of human rights violations identified by the Oaxaca Truth Commission be held accountable. Further recommendations include the development of a mechanism that guarantees the right to the truth, justice and reparation within the framework of transitional justice, as well the evaluation of federal and state-level mechanisms for the protection of journalists and human rights defenders.

- Guarantee the right to protest

Oaxaca is characterized by a long history both of protest and the criminalization of protestors. This tendency was exacerbated 2013, as part of the state’s policy to silence resistance to Peña Nieto’s structural reforms. The detention of teachers and the fabrication of charges against them became a pattern of action at both the state and federal levels.

In May 2013, Oaxacan teachers suffered a wave of arbitrary detentions as a result of their resistance to the educational reform. This onslaught was accompanied by new forms of criminalization: whereas in the past protestors were often accused of terrorism, sabotage and conspiracy, as of 2013 the state began to charge activists with crimes such as kidnapping, organized crime, property damage, money laundering, criminal association and carrying a firearm.

These false accusations serve to demonize and isolate human rights defenders, in a national context of social polarization due to increases in organized crime. The accused are often transferred to maximum security prisons far away from their places of origin, making it more difficult for family members and allies to provide support. Moreover, the government has invested millions of dollars to ensure that news of these arrests and accusations is widely circulated in the mainstream press, generating a high level of discredit for activists.

It is worth noting that on November 24, 2017, a bill to restrict the right to protest was presented in Oaxaca’s State Congress, with the support of the governor. The authors of the Oaxaca citizens’ report warn that if approved, the law would exacerbate social polarization and encourage the excessive use of force that proved to be fatal in the massacre of Nochixtlán.

2018 UPR: Recommendations for improving human rights in Mexico

On November 7, UN Member States issued recommendations regarding the human rights situation in Mexico. The most salient recommendations include: strengthening Mexico’s justice system, including combatting corruption and impunity, ending arbitrary detentions, and establishing an Attorney General that is independent from the executive branch; combatting violence against human rights defenders; and combatting discrimination against Indigenous peoples.

On November 7, UN Member States issued recommendations regarding the human rights situation in Mexico. The most salient recommendations include: strengthening Mexico’s justice system, including combatting corruption and impunity, ending arbitrary detentions, and establishing an Attorney General that is independent from the executive branch; combatting violence against human rights defenders; and combatting discrimination against Indigenous peoples.

These and other recommendations speak directly to the grave human rights violations that took place in Nochixtlán in 2016. What remains to be seen is whether the new administration will heed the UN’s current recommendations and implement the reforms necessary to ensure justice for the victims of Nochixtlán and other episodes of violence perpetrated by the Mexican State.

![]()