Shortly before midnight on September 7, an earthquake with a magnitude of 8.1 on the Richter scale—the strongest to hit Mexico in a century—radiated out from its epicenter in the Gulf of Tehuantepec off the country’s southern coast. Indigenous and farming communities in the marginalized states of Oaxaca and Chiapas bore the brunt of the destruction, with 99 deaths in total.

Shortly before midnight on September 7, an earthquake with a magnitude of 8.1 on the Richter scale—the strongest to hit Mexico in a century—radiated out from its epicenter in the Gulf of Tehuantepec off the country’s southern coast. Indigenous and farming communities in the marginalized states of Oaxaca and Chiapas bore the brunt of the destruction, with 99 deaths in total.

A mere twelve days later, Mexico City residents were busy commemorating the anniversary of the devastating 1985 earthquake when the seismic alarm system sounded, this time in response to a 7.1 magnitude temblor with its epicenter less than 100 miles from the capital. To date the September 19th quake has killed over 300 people and left tens of thousands homeless in Mexico City as well as Mexico State, Puebla, Morelos, and Guerrero.

While news cycles continue to be dominated by delusive coverage of rescue efforts in the capital, distressed communities describe a state of emergency exacerbated by political corruption and opportunistic militarization. The following is a brief overview of the current situation in affected regions, with an emphasis on the perennially overlooked regions of Southeast Mexico.

Devastation on the Southern Coast

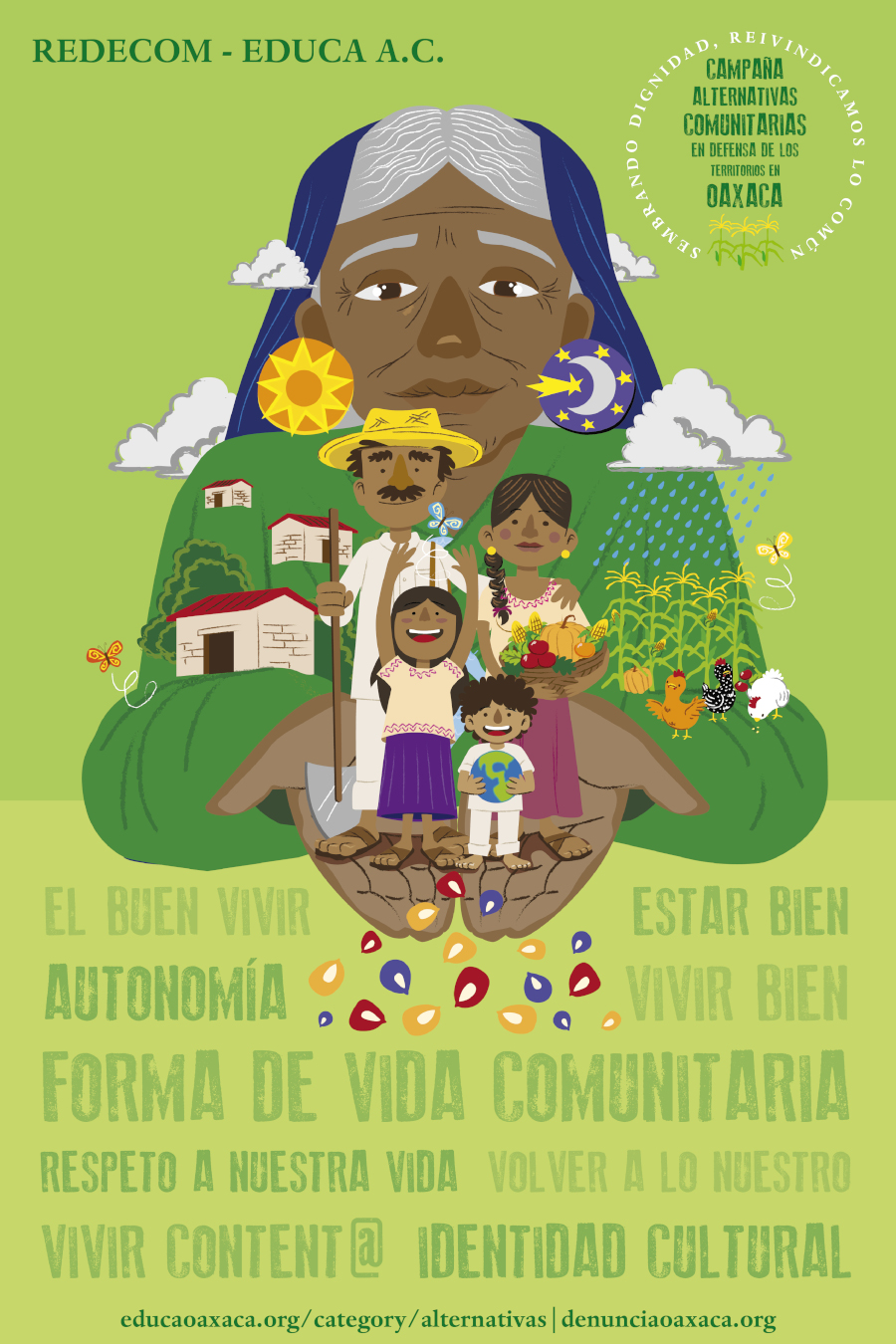

In Oaxaca, the September 7th earthquake and its aftershocks have affected 41 municipalities and caused the deaths of more than 80 people. By far the hardest-hit region is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, where hospitals, schools, and government buildings have been crippled. In the city of Juchitán alone more than 5,000 homes have been reduced to rubble, and displaced residents are living outside in makeshift encampments without reliable access to potable water, electricity, telephone, or Internet—a situation exacerbated this past week by heavy rains and flooding. Meanwhile, more than 4,000 aftershocks have taken their physical and psychological toll on the earthquake-prone region: on September 23, a 6.1 magnitude temblor with an epicenter 12 miles south of Matías Romero toppled already-weakened buildings and roads.

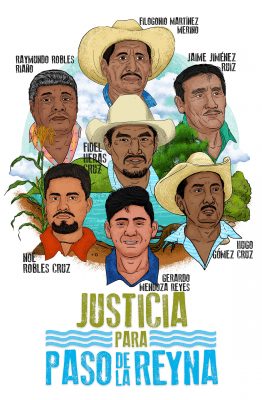

Civil society groups say that endemic corruption has worsened the situation. Non-profit organizations comprising the Humanitarian Aid Observation Mission (MOAH) attest that in the Isthmus, “political candidates and public officials have opportunistically set conditions for humanitarian assistance, which they deliver only to people who are close to the government and political parties.” Moreover, volunteers report harassment and the seizure of vital provisions—a state of affairs enforced by the thousands of military personnel that have filled the region in the wake of the disaster. Oaxacan teachers organized in Section 22 of the National Education Workers Trade Union (SNTE) say this militarization, thinly veiled as humanitarian aid, is merely a “political and economic maneuver by those in power in order to impose the Special Economic Zones.”

The Isthmus—long a geopolitically strategic region since it represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean—has over the past decade been targeted for controversial private development, including the largest wind-power farm in Latin America. MOAH warns that following the September 7th quake,“[s]ome private companies have been playing a leading role in the response” to the disaster, and “[s]ome of these companies have had conflicts in these communities due to the development of megaprojects.”

In Chiapas—one of Mexico’s poorest states, where 76.2% of the population was living below the poverty line in 2014—more than 350,000 families have been affected by the September 7th quake. The most critical areas include the coastal municipalities of Tonalá, Arriaga, and Pijijiapan, where thousands of homes have been damaged and residents have lost what little they own.

Communities and NGOs denounce neglect on the part of authorities, who they say “have not visited homes to evaluate damages, they have not informed people of any rebuilding plans, they have not provided access to shelters, nor have they offered food, medical or psychosocial attention.” Chiapas residents see this lack of attention as a deliberate strategy in the context of land struggles: “If today the government does not arrive to our communities, it is because it is awaiting our extinction in order to extract our natural resources and common goods in the future.”

Reports of political corruption in the context of the 2018 election season echo the situation in Oaxaca: in the municipality of Jiquipilas, only citizens affiliated with the Ecologist Green Party of Mexico have received aid packages. Various reports have emerged of individuals being forced to show their voter cards in order to receive assistance.

Neglect and Anger in the Valley of Mexico

In Mexico City, family members of the missing and volunteer rescue teams continue to clash with armed forces over the premature razing of buildings where many believe that survivors may still be trapped. Meanwhile, the number of homeless and displaced people continues to rise: on September 25, 3,000 residents of the downtown Juarez neighborhood had no other option but to abandon their homes due to around twenty buildings deemed likely to collapse.

While some of the most affected areas of the city include upscale neighborhoods like Roma and Condesa, in Itzapalapa—the most densely populated area of the city where more than a third of residents live in poverty—around 35% of the 8,500 damaged homes are slated to be demolished, and a million and a half people are lacking sufficient potable water. The situation is similar in Xochimilco and other marginalized areas of the city, where residents have denounced the lack of governmental assistance.

In Morelos, 20,000 families were affected by the September 19th quake, with the municipality of Jojutla being particularly hard hit: there 300 homes and stores collapsed, hundreds of buildings are damaged, and families with children have been forced to sleep outside. Residents of this central state say Governor Graco Ramirez is hoarding provisions rather than distributing them to those in need, and even the Diocese of Cuernavaca has accused Ramirez of exploiting the pain of the population for his own political benefit.

In Puebla, where the Governor declared 51% of territories to be in a state of extraordinary emergency, entire towns far from the spotlight have been rendered uninhabitable, and families sleeping outdoors cite a lack of emergency shelters. While some residents have been informed by public officials that their damaged homes would soon be destroyed, they still have not been informed of any reconstruction plans.

People Power

Faced with negligence and corruption, citizens and civil society groups have strengthened grassroots networks of solidarity to support those need and rebuild affected areas. In Oaxaca, communal kitchens have been established in Juchitán, San Dionisio del Mar, and San Mateo del Mar, with the help of dozens of organizations. Architects and builders have joined forces with communities to reconstruct homes in the Isthmus, with an emphasis on preserving traditional and natural building styles and ensuring resilience in the face of future quakes.

In Mexico City, hundreds of designers, coders, and geographers have created #Verificado19S, a “digital platform that verifies and organizes information in order to make the citizen response to the September 19th earthquake more efficient.” The online database maps reports of damages and needs in real time, “coordinates a team to corroborate the information in the field,” then publishes verified reports via Twitter. With trust in the political system at an all-time low and faith in autonomous organization on the rise, it remains to be seen what effects the earthquakes may have on Mexico’s upcoming election season.

Read more:

Anger at response to Mexico earthquake could bring political aftershocks (The Guardian)

In Mexico, Solidarity Versus the State (NACLA)

Oaxaca: Geopolitics and the Earthquake (Desinformémonos – Enemigo Común)

![]()