The following is a translation of the statement read at the closing ceremony of the conference, “Communal Maize from Oaxaca for the World,” held September 27 – 28, 2019 in Oaxaca City in commemoration of National Maize Day.

“… Quetzalcoatl put maize on the lips of the first men, Oxomoco and Cipactónatl, an ancient pair of human beings, corn growers, so that by eating it they would become strong.”

On September 27 and 28, 2019, Indigenous farmers from the state of Oaxaca gathered for the conference “Communal Maize from Oaxaca for the World,” with the purpose of analyzing the current government’s agricultural policies, reflecting on threats of biopiracy in the region and proposing alternatives in the face of an onslaught against native maize and small-scale farming.

On September 27 and 28, 2019, Indigenous farmers from the state of Oaxaca gathered for the conference “Communal Maize from Oaxaca for the World,” with the purpose of analyzing the current government’s agricultural policies, reflecting on threats of biopiracy in the region and proposing alternatives in the face of an onslaught against native maize and small-scale farming.

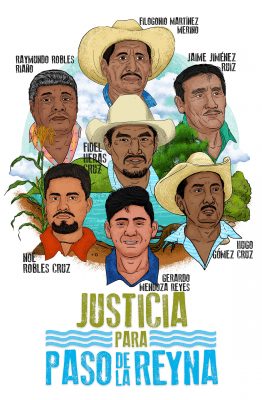

From 2006 to 2015, North American scientists committed a series of grievances against Indigenous Mesoamerican communities under the guise of science and development. The result is a patent application for the genetic characteristics derived from olotón maize, which was taken from the Mixe community of Totontepec and whose existence has been documented since the 1950s in Guatemala and Mexico.

We are concerned about the international regulations that Mexico is pushing to ratify, such as the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Convention of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV 1991), which is bound by the new trade treaty with the United States and Canada (TMEC). These are instruments that legitimize the plundering of genetic resources under the guise of a supposed distribution of benefits on the one hand and, on the other, criminalize the free exchange of seeds in order to favor the interest of transnational corporations. Such regulations underestimate the fact that maize is a Mesoamerican creation that took thousands of years to produce—a creation which companies now seek to appropriate in order to make a profit.

We qualify efforts to patent olotón maize as an act of biopiracy, and we assert that the Universities of California – Davis and Wisconsin – Madison, at the service of the company Mars Inc., did not make any “discovery.” Rather, they have sought to appropriate our ancestral knowledge, showing a contempt for traditional science which in our communities is expressed as custom.

The traditional cultivation of maize in unison with other crops is a practice that has always contributed to the cooling of the planet. Today, the technology developed by western science has understood how olotón maize is nourished by nitrogen, which is captured by bacteria living in the mucilage surrounding its roots. Scientists and companies have also understood how this quality might be manipulated to reduce the use of fertilizers made from petroleum. However, none of this gives them the right to appropriate ancient knowledge, which from an Indigenous perspective must remain in the hands of the communities who work the land to produce their food.

We disapprove of the agricultural and rural land policies promoted by the current Mexican government. Under the guise of combating poverty these paternalistic policies individualize the delivery of minimum resources to farmers, thereby fostering the disintegration of communal life and dealing a blow to the collective rights of Indigenous peoples. While the present administration promises to recognize the self-determination of Indigenous peoples, it in fact imposes programs that destroy communality in the name of transformation.

We disapprove of the agricultural and rural land policies promoted by the current Mexican government. Under the guise of combating poverty these paternalistic policies individualize the delivery of minimum resources to farmers, thereby fostering the disintegration of communal life and dealing a blow to the collective rights of Indigenous peoples. While the present administration promises to recognize the self-determination of Indigenous peoples, it in fact imposes programs that destroy communality in the name of transformation.

We see that the “Sowing Life” program intends to divide communal lands in order to lay the foundations for their future privatization. This is because the program ignores the existence of our community assemblies by promoting decision-making in small groups. The program also promotes the establishment of commercial plantations that seek to replace our traditional cornfields.

The growing import of genetically modified meets the demand for animal feed on farms that have moved from the United States to Mexico. These have already caused serious problems of contamination and even the appearance of diseases caused by the intensive use of antibiotics to raise pigs, chickens and cattle in overcrowded conditions.

Mexico produces the maize it needs to eat, but global policies of comparative advantage want us to stop producing our own food. And so, Mexico exports fruit and vegetables that need large quantities of water for their production, and we import grains that comprise the daily diet of the majority of the population.

The germplasm banks that have been created on the basis of the thousands of collections that have been made in recent years through seed fairs organized by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT) and by the Mexican government’s National Seed Inspection and Certification Service (SNICS) and the National Institute for Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP), among other institutions and with the participation of researchers without professional ethics, have only served to concentrate the genetic diversity of the region.

The germplasm banks that have been created on the basis of the thousands of collections that have been made in recent years through seed fairs organized by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT) and by the Mexican government’s National Seed Inspection and Certification Service (SNICS) and the National Institute for Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP), among other institutions and with the participation of researchers without professional ethics, have only served to concentrate the genetic diversity of the region.

Biotechnology, as well as digitized and robotized agriculture are not the panacea to save the planet from hunger; they are false solutions that only intend to concentrate food production in the hands of fewer and fewer transnational corporations that seek to control our lives.

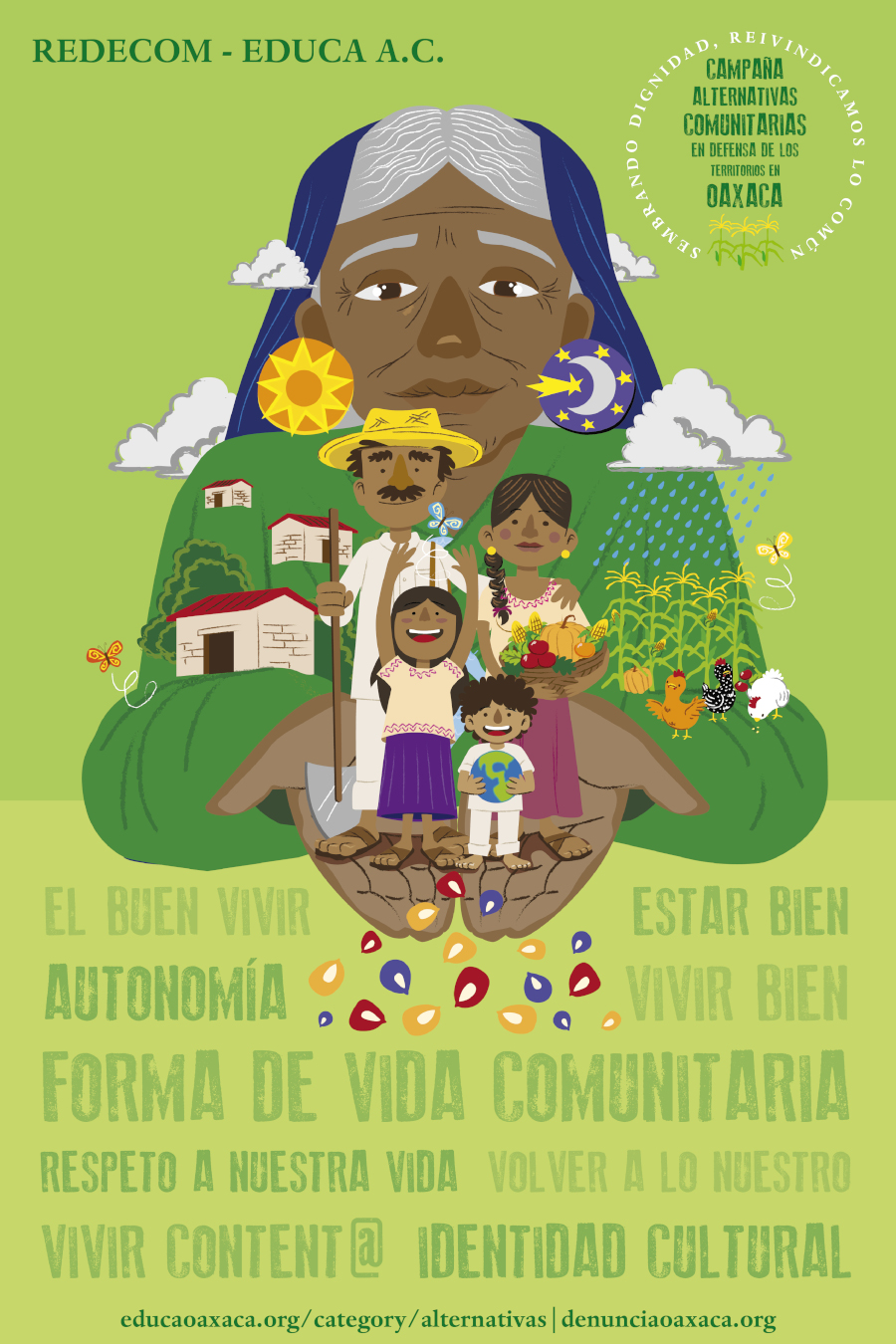

For this reason we make an appeal to Indigenous and farming communities to continue practicing communality as a way of life, to sow their own seeds and to use ancestral and agro-ecological techniques for the production of their food. The self-determination of our peoples will only be possible to the extent that we make food sovereignty possible. For our peoples, the exercise of politics goes beyond participating in an election; let us put this into practice by sowing our seeds and consuming the food that comes from them.

We ask the scientific community to act with an ethic of respect for traditional knowledge and to put itself at the service of peoples seeking solutions to our problems. When scientists have the possibility of using frontier knowledge, we ask that the results of their research and proposals are respectful of nature.

We make an appeal to Oaxacan teachers to use maize as a key element for educating girls, boys and young people.

And we demand that the Mexican government stop pretending to support rural territories and start letting Indigenous and farming peoples make decisions regarding the production of their own food.

Communal maize is a practice, a way of sharing, a way of life. In Oaxaca, communal maize is not about money or profit but rather Guelaguetza, or the system of mutual cooperation maintained by neighbors.

We declare ourselves conservers of the seeds that the planet needs in order to avoid the problems that we are already confronting.

Today we deliver our seeds of olotón maize, as well as the seeds of other maize varieties and plants, to Via Campesina, the most important peasant organization in the world, so that interested farmers can plant them it in their respective countries without having to buy them from transnational companies. It is up to these farmers to plant the seeds, make them bloom and reproduce them so as to adapt them to their circumstances.

May the seeds be free so that free peoples may flourish. Communal maize, communal land!

Native seeds are not commodities! Let’s globalize the struggle and globalize hope!

Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca, Mexico, September 28, 2019

State Space in Defense of the Native Maize of Oaxaca

![]()